The American Chestnut Project

History

Background on American chestnut and chestnut blight

- Listen to "Chestnut Tree" (Helen's Song)

Inspired by the stories told by Helen Titch Nichols, born in 1924

History of the American chestnut and the chestnut blight

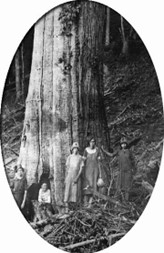

Before the turn of the 20th century, American chestnuts (Castanea dentata) were one of the dominant tree species within the eastern U.S. forests, making up approximately 25% of the trees in its natural range. Over 3 billion American chestnut trees were found in mixed hardwood forests with oaks (Quercus spp.), maples (Acer spp.), and hickories (Carya spp.). Because it could grow rapidly and attain huge sizes, the tree was often the outstanding visual feature in both urban and rural landscapes. The wood was used wherever strength and rot-resistance was needed.

In colonial America, chestnut was a preferred species for log cabins, especially the

bottom rot-prone foundation logs. Later posts, poles, flooring, and railroad ties

were all made from chestnut lumber.

In colonial America, chestnut was a preferred species for log cabins, especially the

bottom rot-prone foundation logs. Later posts, poles, flooring, and railroad ties

were all made from chestnut lumber.

The edible nut was also a significant contributor to the rural economy. Hogs and cattle were often fattened for market by allowing them to forage in chestnut-dominated forests. Chestnut ripening coincided with the Thanksgiving-Christmas holiday season, and turn-of-the-century newspaper articles often showed train cars filled to overflowing with chestnuts rolling into major cities to be sold fresh or roasted. The American chestnut was truly a heritage tree.

This photo shows a surviving 85-foot American chestnut tree in Atkinson, Maine. Photo courtesy of Eric Evans of the Maine Chapter of The American Chestnut Foundation.

All of this began to change at or slightly before the turn of the 20th century with the introduction of Cryphonectria parasitica, the causal agent of chestnut blight. This fungus reduced the American chestnut from its position as the dominant tree species in the eastern forest to little more than an early-succession-stage shrub. There has been essentially no chestnut lumber sold in the United States for several decades and the bulk of the annual 20-million-pound nut crop now comes from introduced chestnut species or imported nuts.

Despite its decimation as a lumber and nut-crop species, the American chestnut has not gone extinct. The species has survived by sending up stump sprouts that grow vigorously in logged or otherwise disturbed sites, but inevitably succumb to the blight and die back to the ground. The most recent USDA Forest Service survey for New York State indicates that there may be as many as 60 million of these sprout clumps in New York, a rich gene pool for starting a restoration effort.

Utilization of Chestnut

Lumber

Chestnut heartwood is legendary for its rot resistance. Standing dead trees and fallen stumps were logged for decades after the chestnut trees were killed. Like redwood, lumber from chestnut heartwood does not need to be pressure treated before being used, and it will not leach any toxic compounds upon weathering. In an increasingly environmentally conscious society, marketing a naturally rot resistant alternative to both pressure treated lumber and old-growth redwood lumber should be easy.

Nut crop

Despite its relatively rapid growth, it will be many decades before plantations or hedgerows of chestnut begin producing significant quantities of timber. However, unlike many other timber-tree species, American chestnut also produces edible nuts. Flowering begins in as little as five years, and as trees mature, crops become frequent and copious. These can serve as a cash crop while the trees mature. Marketing the nuts will be even easier than the lumber. Not every new crop has its own Christmas carol already ingrained into the culture!

Biomass

A third use for the species is to produce biomass for an alternative energy source. Chestnut coppices vigorously, exhibits rapid juvenile growth, and has higher specific gravity than many of the other candidates for biomass production. It also performs well on dry upland ridges where other biomass tree species, such as poplar or willow, would fail.

Enhancement of biodiversity

An important attribute in forested ecosystems is biodiversity. In addition to directly

increasing biodiversity by reestablishing an important forest ecosystem species, reintroducing

the American chestnut may have a positive effect on wildlife populations. In many

forest ecosystems, various oaks have replaced the American chestnut as the primary

mast producers. However, oaks are notorious for producing sporadic mast crops. Before

the blight, chestnut produced a large mast crop nearly every year. This large and

predictable crop was stored away by squirrels and other rodents, and consumed in large

quantities by deer, bears, turkeys, and many other wildlife species to fatten up for

the winter.

An important attribute in forested ecosystems is biodiversity. In addition to directly

increasing biodiversity by reestablishing an important forest ecosystem species, reintroducing

the American chestnut may have a positive effect on wildlife populations. In many

forest ecosystems, various oaks have replaced the American chestnut as the primary

mast producers. However, oaks are notorious for producing sporadic mast crops. Before

the blight, chestnut produced a large mast crop nearly every year. This large and

predictable crop was stored away by squirrels and other rodents, and consumed in large

quantities by deer, bears, turkeys, and many other wildlife species to fatten up for

the winter.