SUNY ESF

Field Notes

A peak into the field work behind the research: How Cranberry Lake white-throated sparrows can help us understand the influence of behavior on disease spread in wild birds (Rhia Henderson | Fall 2025)

Amongst the forest and bogs of Cranberry Lake, you will likely hear the distinct call of the white-throated sparrow singing “Oh Canada, Canada, Canada”. In addition to being adored by professional birders and backyard appreciators alike, this species is important to the research of avian health due to their genetics. Cranberry Lake is a mating ground for migratory white-throated sparrows, and there has been a project studying them at CLBS for nearly 30 years, that Dr. Chris Briggs of SUNY ESF became the primary investigator of two years ago, and I joined to continue the research on these fascinating little birds.

Photos by C. Briggs: A beautiful example of a white-throated sparrow

Photos by C. Briggs: A beautiful example of a white-throated sparrow

I should probably make it clear before I show you too many photos that we were heavily permitted to be handling live wild birds, and I received extensive training from Dr. Briggs, an ornithologist and the beloved ESF introductory biology professor. All the images you see of us handling and trapping birds were done with the highest level of precaution for the safety and health of the birds in our care, and all birds were released after their alien abduction experience.

Photo by C. Briggs: A tan-stripe and white-stripe pair. Each morph can have some variation, and this couple depicts a particularly dull and particularly bright variation each.

The White-throated sparrow has two color morphs, white-stripes and tan-stripes which reference the color of the stripe above the bird’s eye. Males and females look the same, and both sexes could be either white- or tan-striped. The white-striped variation occurred from a genetic mutation a couple of million of years ago, that attaches their coloring with certain behavioral traits including aggressiveness and promiscuous breeding. In contrast, the tan-stripes are more territorial and tend to mate monogamously. This species avoids splitting into two distinct species because they mate across morphs, meaning that white-striped males will mate with tan-striped females, and vice versa.

Photo by C. Briggs: Rhia draws blood from a bird’s wing while undergraduate researcher Artie takes careful notes.

So, you may be asking how these funky genetics and the mating habits of birds are important in the bigger picture of science. The white-throated sparrow allows me to research how different mating behaviors can affect disease risk by increasing the possibility of an individual contracting diseases through promiscuous mating or aggressive behaviors, or if behavior is associated with changes in immune function. These questions can provide a baseline for questions around managing potential pandemics like avian flu, and pre-emptive actions to conserve species that are more at risk of these diseases due to their innate behaviors.

When I arrived at CLBS in May, our team was one of the first groups to move in for the season, before even the administrative team and any campers. With mornings still brisk and dark, and the camp quiet, our early hikes out to the bog in search of that distinct call were a moment of peace for me. I had heard the white-throated sparrow song hundreds of times in my backyard or on hikes, but there is something different about hiking out along the edge of Sucker Brook and hearing that lilting song breaking through the dawn.

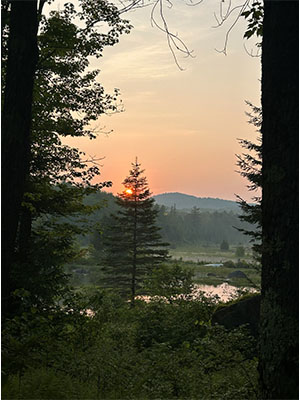

Photo by R. Henderson: Dawn over Forsayth’s Bog

Photo by C. Briggs: Rhia removes a bird from the nearly-invisible mist-net.

Our team of myself, Dr. Briggs, and my undergraduate research assistant Artemis (Artie) became lovingly known as “The Bog People” by campers due to the extensive time we spend in the bogs around CLBS, and the clothing we wore to protect ourselves from the incessant bugs, where not an inch of bare skin was ever visible and made us look like cryptid bog creatures. Along with my own research, I trained and supported Artie on a project they designed looking at how song quality related to immune function and parasite infection rates.

Photo by R. Henderson: Here Artie and Chris wait in full bug and rain gear for a bird to fly into our mist net.

Photo by R. Henderson: An example of the gear that was carried with us every day. A cooler for our blood samples, the Mary Poppins style pack that carried everything from tiny colored bird bands to our 20-foot nets, and metal extendable stakes to support the nets.

Photo by C. Briggs: Rhia using recorded calls to assess an area for white-throated sparrow presence. The birds are reactive during mating season, and will come close or call back to a recorded call if they’re nearby

Most mornings we were up by 3:30-4am, with the goal of arriving at our field site for the day just before sunrise. We trekked through thick forests, flooded bogs, and across streams with extensive gear. Some days we knew where we were going, other days were a pure adventure, stopping our hike when we heard or saw the birds, or we occasionally used audio recordings on our phones to bring them in to us when we suspected they may be nearby. Bog-walking was a point of endless frustration and amusement, because you would be walking easily then your foot would be sucked into the sphagnum moss up to your hip with no warning. As you can imagine, a boot dryer was our best friend.

Due to the early mornings, we tended to get pretty goofy in the field with lots of running jokes and occasionally giving students of the field station a fright by appearing in unexpected locations.

Photo by A. Heppner: Due to the intense blackflies in the Forsayth’s bog, we had to get creative to figure out how to eat without being eaten.

Photo by A. Heppner: After finding ourselves on a soft moss bed to trap a breeding pair of birds, we took a moment to become one with the moss.

Photo by E. Arsenault: Rhia gives a presentation in the CLBS dining hall

We also were an integrated part of the CLBS community, taking part in camp activities, rescuing birds from classrooms, and giving demonstrations of bird banding around the campus. I also gave a talk during Session B on the potential impacts from nematodes (wormlike parasites) on bird health to students, staff, and the greater CLBS community, and was a guest instructor during the Wildlife Techniques course taught by Dr. Nate Wehr during session C, where I taught students about bird banding and ethics in wildlife research.

While this is a very brief introduction to my research and my time at CLBS, the location and people allowed me to conduct a study that is truly unique and will be impactful across birds species nationwide. I look forward to getting back to this great camp in the future!

Fall 2024

It’s impossible to traverse the streams surrounding Cranberry Lake without acknowledging the presence of beavers. These powerful ecosystem engineers create drastic changes in their surrounding landscape with their dams, and in the Adirondack region, these dams are everywhere. Dense forests are transformed into lush meadows. Even after dams are abandoned or washed out, the impacts of the beavers remain, as forest regrowth is a gradual process. As a new graduate student interested in food web ecology, I became fascinated with the impacts of ecosystem change perpetuated by beaver dams on aquatic food webs. Namely, the food sources of the ubiquitous macroinvertebrates found in Adirondack streams.

To answer this complex question, myself and two undergraduates at SUNY ESF, Kendal Massey and John Donnelly, sampled aquatic macroinvertebrates in three different types of streams: streams with intact beaver dams, streams with recently breached dams due to flooding, and streams in recovery from damming. These streams serve as tiles in a mosaic that will offer a picture of temporal change before and after a beaver dam breach.

John on an intact beaver dam on Sucker Brook. Photo taken by K. Massey.

A former dam on Sucker Brook breached in August 2023 due to a major flood event. Photo taken by A. Hullihen

Location of a former beaver dam on Chair Rock Creek, where the forest opens up to

a meadow. Photo taken by A. Hullihen

Location of a former beaver dam on Chair Rock Creek, where the forest opens up to

a meadow. Photo taken by A. Hullihen

The majority of streams we worked on over the course of the summer near Cranberry Lake were not accessible by trail, so a large portion of our project was made possible by Kendal, who headed bushwhacking navigation. This bushwhacking was often very difficult, as we had a lot of equipment including bulky nets, rafts, and hand-made invertebrate samplers.

Kendal and I enjoying the ease of trail hiking near East Creek. Photo taken by J. Donnelly

Kendal and I bushwhacking over a beaver dam on East Creek. Photo taken by J. Donnelly

Completed Hester-Dendy samplers hand-made by A. Hullihen, K. Massey, and E. Hughes.

A total of 45 samplers were deployed over the summer. Photo by A. Hullihen.

Completed Hester-Dendy samplers hand-made by A. Hullihen, K. Massey, and E. Hughes.

A total of 45 samplers were deployed over the summer. Photo by A. Hullihen.

Working with the invertebrates both in and out of the field was one of the most rewarding processes throughout the summer. Witnessing first-hand the diversity of these invertebrates within and between streams and learning to identify them improved my skills as a scientist greatly.

Kendal and I using D-nets to sample invertebrates on East Creek. Photo by J. Donnelly.

An angry dragonfly nymph (Cordulegaster) in the lab during the insect identification process. Photo by A. Hullihen.

Overall, the summer was an incredible period of learning and growth as a scientist made possible by three people willing to go the distance mentally and physically for this complex question. It would not have been possible without a team, and I am eternally grateful to Kendal and John for their great work.

The dream team on Chair Rock Creek. Photo by B. Spitz.

The dream team on Chair Rock Creek. Photo by B. Spitz.

Abby is an MS student in Dr. Emily Arsenault’s lab in the Department of Environmental Biology at SUNY ESF. Abby’s work was made possible by a Samuel Grober (’38) Graduate Fellowship awarded in 2024.

A Typical Day in the Field for an Undergraduate Research at CLBS

By Matthew Norvilitis | Fall 2024

Jack Marshall, a graduate student in the Arsenault freshwater ecology lab, and I would wake up around 5:30 am in order to have enough time in the field for our day. We would meet at the CLBS Grober Lab to set up our backpacking bags for the day, packing in fishing gear to collect brook trout via angling, a YSI probe to gather limnological profiles, inflatable rafts and paddles to get out on the water, a vertical zooplankton net to get plankton for trophic level baselines, watertight jugs for water quality analysis, small coolers to keep our fish and water samples fresh, equipment to field process brook trout, food for lunch and dinner, safety equipment and sometimes camping stuff to stay the night. With all of this gear distributed across only two backpacking backpacks, we had some extremely heavy loads to carry, sometimes weighing over 55lbs. We would then hop on one of the CLBS boats to drive to the part of the lake that was nearest to the pond, we would anchor and head to the trailhead where a 2-4 mile one way trip awaited us. We would arrive, set up our gear and get to sampling for the day. We would fish, and do limnological work for 8-14 hours before our 2-4 mile hike back to the boat. Once we arrived back at the station we would prep our samples for storage by transferring zooplankton, and macroinvertebrates to ethanol, filtering and prepping our water quality samples and by dissecting and freezing our samples. To round out many of the field days Jack and I would work together to finish data input before eating dinner and going to bed. These field days were long and tested our patience and sometimes our sanity. Occasionally, Jack and I would take limnological information at night, and/or not have enough time to hike back to the boat, so we would camp out in the field. All of those days were incredibly fun, yet grueling as they had the heaviest packs of all. Though tough, those field days were a dream and I will never forget all of the amazing times in the NY backcountry.

Jack Marshall and Matthew Norvilitis conducting Adirondack brook trout research based at CLBS

Photo Credit: Matt and Jack

Matthew is an undergraduate student in Dr. Emily Arsenault’s lab in the Department of Environmental Biology at SUNY ESF. Matt’s summer research was funded by the ESF Career Center and the SUNY Chancellor’s Summer Research Excellence Fund.

Fall 2023

The sign at the trailhead announced that we were “Entering Grizzly Country.” As my spouse and I hiked through the forest in Montana’s Glacier National Park, I ruminated on a thought experiment: What would it mean to have literally crossed over into a sovereign entity called “Grizzly Country”?

The sign suggested I was crossing a threshold into wild space of threat, akin to settler-colonial notions of “Indian Country,” where the protections and constraints of “civilization” no longer apply. “You are entering a wilderness area and must accept certain inherent dangers,” the sign warned. “There is no guarantee of your safety. Bears have injured and killed visitors and may attack without warning and for no apparent reason.”

But what if we took seriously the sovereignty of the bear, recognized its authority, walked humbly through the woods, aware that one is in someone else’s place? Since that hike, I have not been able to get the question out of my mind: could scholars of International Relations like myself acknowledge political agency and sovereignty of wild animals?

To find out, I decided to go to black bear country, immersing myself into the Ursus americanus habitat surrounding ESF’s Cranberry Lake Biological Station (CLBS) and Newcomb campus, ancestral lands of the Mohawk Nation of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, New York’s Adirondack region.

As I hiked through woods and wetlands, I struggled with research methods: How could I ethically and effectively study the politics of our relationship with the more-than-human world? My discipline of Political Science (and the social sciences more generally) often ignores the natural world as an inert terrain on which politics happens. Our research methods focus on people, rather than the environments in which we are embedded.

Conversely, many ecological studies of bears reproduce a one-way relationship of humans over bears. We sedate them. Collar them. Dissect them. Preserve their skills and skins. While these methods have generated invaluable science, they also replicate settler-colonial power relations – in which my own family history is complicit – that treat nature as a resource to be dominated. Data is extracted from bears for our understanding.

Seeking alternatives, I was inspired by the writings of Robin Wall Kimmerer, Director of ESF’s Center for Native Peoples and the Environment (CNPE), who drew my attention to Indigenous conceptions of the world as a space of reciprocal obligations. What if bears are my relatives? I wouldn’t collar a family member! I was delighted to find Professor Kimmerer at CLBS during my stay. She urged me to think about what in Braiding Sweetgrass she calls “honorable harvest” of scientific data (pp. 174-201). As we seek to understand the more-than-human world, how do we act with respect and care?

I thought too about Jane Goodall’s imaginative reapplication of ethnographic techniques developed for studying human societies to understand the world of non-human primates. While ethnography has a colonial history of its own, its best examples involve getting off the verandah, out of the lab and into the world of the “Other.” Good ethnography places the researcher into spaces they can’t control, where research “subjects” have agency to conceal, refuse, even dupe. Or reveal their world if they choose.

But what would an ethical ethnography of Bear Country look like? Wild black bears don’t like human company and they certainly wouldn’t sit for a key informant interview!

Instead, I walked the trails of CLBS and Newcomb campus, looking for bear sign – tracks, scat, scratches on trees, torn up logs – trying to discern patterns of meaning on the landscape. A book I found in the CLBS library – Paul Rezendes’ Tracking and the Art of Seeing – suggested these traces formed a kind of unintentional text: “Tracking an animal is opening the door to the life of that animal. It is an educational process, like learning to read. In fact, it is learning to read. Following an animal’s trail may bring you closer to the animal physically, but more important, it brings you closer to it in perception” (p. 15).

Of course, walking in Bear Country also meant that occasionally I would encounter

bears themselves. On a trail through State lands just outside ESF’s Newcomb campus,

I heard a rustling in the ferns and then a bear popped out just 100 feet behind me.

I followed the standard advice in books like Bear Aware: The Quick Reference Bear

Country Survival Guide – held my ground, clapped loudly, made myself look big and

shouted “GO AWAY!” It turned to look at me, sniffed the air and then startled, running

off into the woods.

Reflecting on this experience later, I felt troubled. I wanted to keep myself safe,

but I would not tell humans I am learn from to get lost as soon as I saw them! How

might I translate normal protocols of human subject research to wildlife?

I decided I would observe bears’ “public behavior.” But I would maintain a distance of at least 300 yards – the required viewing distance in Denali National Park – when watching a bear. If the animal walked away, I would not follow, interpreting it as equivalent to a human interviewee’s withdrawal of consent. I would only backtrack fresh bear sign, rather than following it.

I also rethought my script, words to recite when in bears’ proximity. I wanted to alert them to my presence, keep them from coming closer, but also express gratitude. “Before all else,” ESF’s Neil Patterson says in an exhibit at the Adirondacks’ Wild Center, “give thanks.” In his Haudenosaunee tradition of the Thanksgiving Address, one must greet and express appreciation for all the beings that surround us as kin.

And so, arriving at the beaver dam on CLBS’s Whoosh Pond, I saw an adult black bear feeding at the far edge of the wetland, a safe distance of water between us. I clapped loudly, but this time I thought of it as appreciative applause. I shouted, but I thanked the bear for her help with my research. She looked in my direction. Then returned to browse.

Emerging from the shore, she stretched, marking a conifer with her claws. A few minutes later, a cub joined her. I shouted again, acknowledging that I was in their domain. I meant no harm. I apologized for the injury caused to bears by my people. I hoped what I learned from them would be useful to them.

I watched for twenty minutes. It was raining, but I was elated. They then disappeared,

off into the forest. I returned to my cabin.

I belong to a separate domain than the bear; I must not grasp nor over-relate. But

through careful choreography and respectful observation, perhaps I can ask the bear

to teach me – at a distance – about her world, that of swamp plants and berries, beechnuts

and wild sarsaparilla.

In return, I can communicate with my own human communities about the duties we have to her and the more-than-human world she inhabits. And I must resist the systems of colonialism and environmental destruction that privilege my white settler body over that of other beings. My work must contribute to recognition of the sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples who have had entwined relations of obligation with bears in these lands since time immemorial.

Dr. Matthew Breay Bolton is enrolled in SUNY ESF’s MS in Environment Studies. He is Professor of Political Science at Pace University in New York City; author of Political Minefields: The Struggle against Automated Killing and Imagining Disarmament, Enchanting International Relations. Bolton was part of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) team awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017.

My name is Kate Henderson, and I am a PhD student in Josh Drew’s lab at ESF. My research focuses on fish biodiversity and ecosystem services across New York, and I spent an incredible summer at Cranberry Lake surveying the fish communities there. While we may think of Adirondack Lakes as being pristine, they have experienced major anthropogenic changes, from acid rain to introduced species. Cranberry Lake has seen the introduction of predators such as bass and northern pike, and my surveys yielded far fewer native species such as minnows and white suckers than early DEC surveys prior to the arrival of the introduced predators. However, interviews with anglers revealed that the bass are highly valued species that people have fished for on the lake for decades. People who fish on the lake were knowledgeable about the species in it and their population trends, and valued having a healthy lake to spend time on with their families and to be there for generations to come. The combination of biological surveys and interviews reveals the importance of maintaining landscapes that preserve biodiversity while also meeting human needs. Undergraduate Students Jordyn Worshek and Jamie Schultz did fish research alongside me investigating the high rate of cataracts in Cranberry Lake fish and the potential causes of this phenomenon- stay tuned for their results! Cranberry Lake is a beautiful site, and I felt very lucky to spend the summer at the biological station there!

Kate Henderson is a PhD student in the Department of Environmental Biology at SUNY-ESF and received a scholarship from CLBS to support her research during summer 2023.