The American Chestnut Project

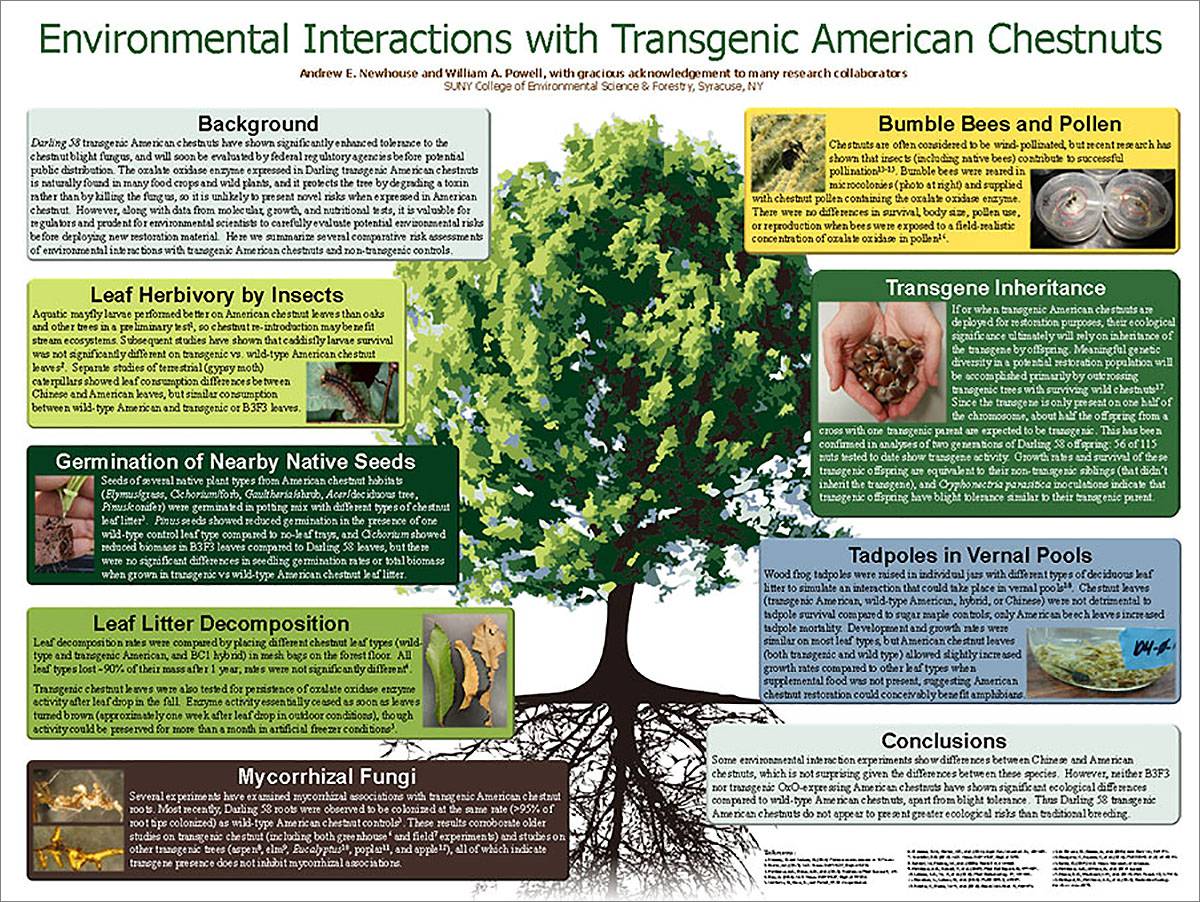

Environmental Interactions with Transgenic American Chestnuts

Environmental Interactions with Transgenic American Chestnuts Andrew E. Newhouse and William A. Powell With gracious acknowledgement to many research collaborators SUNY College of Environmental Science & Forestry, Syracuse, NY

Background

Darling transgenic American chestnuts have shown significantly enhanced tolerance to the chestnut blight fungus, and will soon be evaluated by federal regulatory agencies before potential public distribution. The oxalate oxidase enzyme expressed in Darling transgenic American chestnuts is naturally found in many food crops and wild plants, and it protects the tree by degrading a toxin rather than by killing the fungus, so it is unlikely to present novel risks when expressed in American chestnut. However, along with data from molecular, growth, and nutritional tests, it is valuable for regulators and prudent for environmental scientists to carefully evaluate potential environmental risks before deploying new restoration material. Here we summarize several comparative risk assessments of environmental interactions with transgenic American chestnuts and non-transgenic controls.

Leaf Herbivory by Insects

Aquatic mayfly larvae performed better on American chestnut leaves than oaks and other

trees in a preliminary test1, so chestnut re-introduction may benefit stream ecosystems. Subsequent studies have

shown that caddisfly larvae survival was not significantly different on transgenic

vs. wild-type American chestnut leaves2. Separate studies of terrestrial (gypsy moth) caterpillars showed leaf consumption

differences between Chinese and American leaves, but similar consumption between wild-type

American and transgenic or B3F3 leaves.

Aquatic mayfly larvae performed better on American chestnut leaves than oaks and other

trees in a preliminary test1, so chestnut re-introduction may benefit stream ecosystems. Subsequent studies have

shown that caddisfly larvae survival was not significantly different on transgenic

vs. wild-type American chestnut leaves2. Separate studies of terrestrial (gypsy moth) caterpillars showed leaf consumption

differences between Chinese and American leaves, but similar consumption between wild-type

American and transgenic or B3F3 leaves.

Bumble Bees and Pollen

Chestnuts are often considered to be wind-pollinated, but recent research has shown

that insects (including native bees) contribute to successful pollination13-15. Bumble bees were reared in microcolonies (photo at right) and supplied with chestnut

pollen containing the oxalate oxidase enzyme. There were no differences in survival,

body size, pollen use, or reproduction when bees were exposed to a field-realistic

concentration of oxalate oxidase in pollen16.

Chestnuts are often considered to be wind-pollinated, but recent research has shown

that insects (including native bees) contribute to successful pollination13-15. Bumble bees were reared in microcolonies (photo at right) and supplied with chestnut

pollen containing the oxalate oxidase enzyme. There were no differences in survival,

body size, pollen use, or reproduction when bees were exposed to a field-realistic

concentration of oxalate oxidase in pollen16.

Germination of Nearby Native Seeds

Seeds of several native plant types from American chestnut habitats (Elymus/grass,

Cichorium/forb, Gaultheria/shrub, Acer/deciduous tree, Pinus/conifer) were germinated

in potting mix with different types of chestnut leaf litter3. Pinus seeds showed reduced germination in the presence of one wild-type control

leaf type compared to no-leaf trays, and Cichorium showed reduced biomass in B3F3

leaves compared to Darling leaves, but there were no significant differences in seedling

germination rates or total biomass when grown in transgenic vs wild-type American

chestnut leaf litter.

Seeds of several native plant types from American chestnut habitats (Elymus/grass,

Cichorium/forb, Gaultheria/shrub, Acer/deciduous tree, Pinus/conifer) were germinated

in potting mix with different types of chestnut leaf litter3. Pinus seeds showed reduced germination in the presence of one wild-type control

leaf type compared to no-leaf trays, and Cichorium showed reduced biomass in B3F3

leaves compared to Darling leaves, but there were no significant differences in seedling

germination rates or total biomass when grown in transgenic vs wild-type American

chestnut leaf litter.

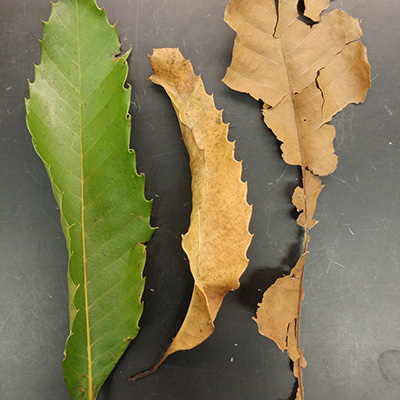

Leaf Litter Decomposition

Leaf decomposition rates were compared by placing different chestnut leaf types (wild-

type and transgenic American, and BC1 hybrid) in mesh bags on the forest floor. All

leaf types lost ~90% of their mass after 1 year; rates were not significantly different4.

Leaf decomposition rates were compared by placing different chestnut leaf types (wild-

type and transgenic American, and BC1 hybrid) in mesh bags on the forest floor. All

leaf types lost ~90% of their mass after 1 year; rates were not significantly different4.

Transgenic chestnut leaves were also tested for persistence of oxalate oxidase enzyme activity after leaf drop in the fall. Enzyme activity essentially ceased as soon as leaves turned brown (approximately one week after leaf drop in outdoor conditions), though activity could be preserved for more than a month in artificial freezer conditions5.

Transgene Inheritance

If or when transgenic American chestnuts are deployed for restoration purposes, their

ecological significance ultimately will rely on inheritance of the transgene by offspring.

Meaningful genetic diversity in a potential restoration population will be accomplished

primarily by outcrossing transgenic trees with surviving wild chestnuts17. Since the

transgene is only present on one half of the chromosome, about half the offspring

from a cross with one transgenic parent are expected to be transgenic. This has been

confirmed in analyses of two generations of Darling offspring: 56 of 115 nuts tested

to date show transgene activity. Growth rates and survival of these transgenic offspring

are equivalent to their non-transgenic siblings (that didn't inherit the transgene),

and Cryphonectria parasitica inoculations indicate that transgenic offspring have

blight tolerance similar to their transgenic parent.

If or when transgenic American chestnuts are deployed for restoration purposes, their

ecological significance ultimately will rely on inheritance of the transgene by offspring.

Meaningful genetic diversity in a potential restoration population will be accomplished

primarily by outcrossing transgenic trees with surviving wild chestnuts17. Since the

transgene is only present on one half of the chromosome, about half the offspring

from a cross with one transgenic parent are expected to be transgenic. This has been

confirmed in analyses of two generations of Darling offspring: 56 of 115 nuts tested

to date show transgene activity. Growth rates and survival of these transgenic offspring

are equivalent to their non-transgenic siblings (that didn't inherit the transgene),

and Cryphonectria parasitica inoculations indicate that transgenic offspring have

blight tolerance similar to their transgenic parent.

Tadpoles in Vernal Pools

Wood frog tadpoles were raised in individual jars with different types of deciduous

leaf litter to simulate an interaction that could take place in vernal pools18. Chestnut leaves (transgenic American, wild-type American, hybrid, or Chinese) were

not detrimental to tadpole survival compared to sugar maple controls; only American

beech leaves increased tadpole mortality. Development and growth rates were similar

on most leaf types, but American chestnut leaves (both transgenic and wild type) allowed

slightly increased growth rates compared to other leaf types when supplemental food

was not present, suggesting American chestnut restoration could conceivably benefit

amphibians.

Wood frog tadpoles were raised in individual jars with different types of deciduous

leaf litter to simulate an interaction that could take place in vernal pools18. Chestnut leaves (transgenic American, wild-type American, hybrid, or Chinese) were

not detrimental to tadpole survival compared to sugar maple controls; only American

beech leaves increased tadpole mortality. Development and growth rates were similar

on most leaf types, but American chestnut leaves (both transgenic and wild type) allowed

slightly increased growth rates compared to other leaf types when supplemental food

was not present, suggesting American chestnut restoration could conceivably benefit

amphibians.

Mycorrhizal Fungi

Several experiments have examin ed mycorrhizal association s with transgenic Ame rican

chestnut roots. Most recently, Darling roots were observed to be colonized at the

same rate (>95% of root tips colon ized) as wild- type American chestnut controls3 . These results corrob orate older studies on transgenic chestnut (inc luding both

greenhouse6 and field7 experiments) and studies on other transgenic trees (aspen , elm , Eucalyptus10, poplar11, and apple12), all of which indicate transgene presence does not inhibit mycorrhizal associations.

Several experiments have examin ed mycorrhizal association s with transgenic Ame rican

chestnut roots. Most recently, Darling roots were observed to be colonized at the

same rate (>95% of root tips colon ized) as wild- type American chestnut controls3 . These results corrob orate older studies on transgenic chestnut (inc luding both

greenhouse6 and field7 experiments) and studies on other transgenic trees (aspen , elm , Eucalyptus10, poplar11, and apple12), all of which indicate transgene presence does not inhibit mycorrhizal associations.

Conclusions

Some environmental interaction experiments show differences between Chinese and American chestnuts, which is not surprising given the differences between these species. However, neither B3F3 nor transgenic OxO-expressing American chestnuts have shown significant ecological differences compared to wild-type American chestnuts, apart from blight tolerance. Thus Darling transgenic American chestnuts do not appear to present greater ecological risks than traditional breeding.

References

1.Sweeney, B. and Jackson, D. (2016) Personal communication to W. Powell

2.Brown, A.J. (2017). M.S. Thesis. SUNY-ESF, Dept. of EFB.

3.Newhouse, A.E., Oakes, A.D., et al. (2018). Frontiers in Plant Science 9, 1–9.

4.Gray, A. (2015). M.S. Thesis. SUNY-ESF, Dept. of FNRM.

5.Matthews, D., Baier, K., and Powell, W. 2013 unpublished.

6.D'Amico, K.M., Horton, T.R., et al. (2015). Appl. Env. Microbiol. 81, 100–108.

7.Tourtellot, S.G. (2013). M.S. Thesis. SUNY-ESF, Dept. of EFB.

8.Kaldorf, M., Fladung, M., et al. (2002). Planta 214, 653–660.

9.Newhouse, A.E., Schrodt, F., et al. (2007). Plant Cell Reports 26, 977–987.

10.Lelmen, K.E., Yu, X., et al. (2010). Plant Biotechnology 27, 339–344.

11.Danielsen, L., Lohaus, G., et al. (2013). PLOS ONE 8, e59207.

12.Schäfer, T., Hanke, M.-V., et al. (2012). Genet. Mol. Biol. 35, 466–473.

13.de Oliviera, D., Gomes, A., et al. (2001) ActaHort. 561, 269-273.

14.Hasegawa, Y., Suyama, Y., et al. (2015). PLOS ONE 10 (3): e0120393.

15.Zirkle, C. (2017) M.S. Thesis. University of Arkansas.

16.Newhouse, A.E., Allwine, A., et al. (2019 in prep)

17.Steiner, K.C., Westbrook, J.W., et al. (2017). New Forests 48, 317–336.

18.Goldspiel, H., Newhouse, A.E., et al. (2018). Restoration Ecologydoi:10.1111/rec.12879.